Harvesting Hope

LEYTE, Philippines — Hundreds of people live in barrack-like bunkhouses made of woven bamboo mats, with clotheslines spread between the temporary buildings, after many families were displaced by Typhoon Yolanda last November.

Some bunkhouses are surrounded by muddy walkways, where the dirt squelches up the side of the residents’ shoes, covering feet with grime. Others have rocky walkways that are cleaner, but uneven.

All of these communities have children who run around and play in the makeshift neighborhoods, attend school in neat uniforms and cheerfully greet visitors with a bright “Hello!”

In her community garden, Lea Encina talks about the fruits and vegetables the bunkhouse residents have planted, harvested, eaten and sold in the past three months.

Still, life can be bleak in these temporary homes, where families are waiting for their lives to begin again after losing all of their belongings in Typhoon Yolanda.

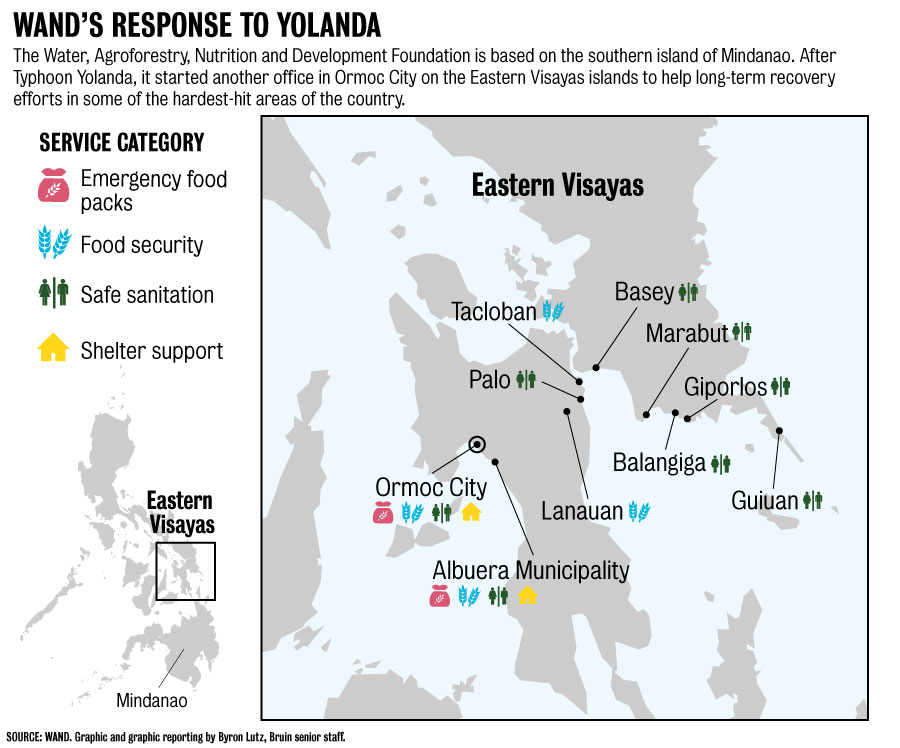

One local organization, the Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation, also known as WAND, provides free trainings for bunkhouse residents, teaching them how to plant their own gardens and cultivate enough crops to feed themselves.

In some bunkhouse communities across the island of Leyte, WAND has used donations from GlobalGiving, including money donated by UCLA students, to provide the seeds to start large communal gardens.

The Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation and Samaritan’s Purse teamed up to sponsor gardens in bunkhouse communities around Tacloban. WAND provided seeds and teaches the skills and techniques necessary to grow several types of vegetables that can be eaten, shared and sold by displaced residents living in temporary housing.

Donors to WAND come from all over the world, and a significant number of them, about 40, have donated through GlobalGiving more than once, Elmer Sayre, WAND’s in-house adviser, said. WAND continues to receive a slow stream of donations each month, ranging from just $50 to $1,000 in a good month, Sayre said.

In November, December and January, people (were) more generous because the typhoon (was) still in people’s minds. Now, we get $50, $100 a month. —Elmer Sayre

That’s why Sayre said WAND may start selling seeds and toilets, which are part of the organization’s push for sanitation, instead of donating them in the future. The trainings will remain free.

“In November, December and January, people (were) more generous because the typhoon (was) still in people’s minds,” Sayre said. “Now, we get $50, $100 a month.”

The Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation teaches displaced persons living in bunkhouses several different styles of gardening.

In places that were unused muddy paths and old sugar cane fields now sprout seedlings of okra, squash, peppers, potatoes, onions and a spinach-like vegetable called kangkong, awaiting harvest by people who can barely afford to buy food at the market.

“I think the reason the people here like gardening is because the gardening is like therapy,” said Nina Herrera, the bunkhouse captain for a community in Tacloban. “It helps them cope with their hardship in life.”

The bunkhouse residents learn to plant crops in several styles, including container gardens, vertical gardens and more traditional row gardens.

I think the reason the people here like gardening is because the gardening is like therapy. It helps them cope with their hardship in life.—Nina Herrera

“People share what they have planted,” said Melissa Pader, camp manager at a bunkhouse near Ormoc City. “Some of them also sell the vegetables. It gave them a way to earn money.”

Earning money is especially important for victims of the typhoon. In the storm, they lost their homes, jobs and livelihoods, and relocation into a bunkhouse can move people far away from the city and coastline, where many jobs exist.

Some lost their businesses, others lost their fishing boats in the storm.

Coconut farmers lost most of their crops, said Sayre. And these people may be out of work for a long time: A coconut tree can take up to 10 years to produce fruit.

Elmer Sayre, with the Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation, designed a water-efficient toilet specifically for residents in the Philippines.

But the seedlings keep the residents from depending on the market for food and give them an opportunity to make money to rebuild homes and buy other necessities, Sayre said.

Samaritan’s Purse, an international nonprofit based in North Carolina, partnered with WAND to scale up Sayre’s attempts to provide toilets to neighborhoods at risk for contaminating fresh water sources and to provide tools for the gardens.

Sayre provided the design for an efficient toilet and Samaritan’s Purse provided the resources and hired Filipinos in the disaster area to produce donated bathrooms, said program director Gavin Gramstad.

Fruits and vegetables grown in gardens sponsored by the Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation are often incorporated into meals such as stew.

Making a bathroom

Toilets made by WAND and Samaritan’s Purse are made through sweat equity. Families are provided assistance and materials but must build the toilet themselves. Each recipient of a toilet must:

- Attend a training to learn about the dangers of defecating in the open.

- Dig a ditch that will hold the septic tank.

- Install the septic tank using bags of sand and gravel.

- Build the structure that surrounds the toilet bowl out of woven bamboo sheets and coco lumber.

- Install the toilet bowl and structure.

“He is so tied into the community. Elmer says exactly what the needs are and how to address them directly,” said Yen Pham, a 2009 UCLA alumna working with Samaritan’s Purse in Tacloban.

The toilets are crucial to keeping illnesses like cholera out of communities that are already very vulnerable to infectious disease, Sayre said.

Samaritan’s Purse hopes to outfit four municipalities with Sayre’s septic tank and bowl designs so that the towns will be completely free of raw sewage by the end of this year. The whole process requires 10,000 donated toilets.

Bunkhouse residents use plastic bottles and old containers to start seedlings that will be transplanted into larger areas.

Samaritan’s Purse enrolls every recipient of a toilet in a class on the role of proper sanitation in water-borne illnesses like cholera that can devastate communities in the Philippines.

For now, the people who have learned to garden from WAND’s trainings are reaping the rewards of their newfound green thumbs.

Most of the first crops were planted in July, and some communities have already come together to harvest two or three sets of vegetables. These gardens brighten the landscape of a handful of bunkhouse communities across the islands of Leyte and Samar.

With harvests once or twice a month, people have plenty of vegetables to eat, and enough left over to sell sometimes, Sayre said.

A shipment of cocolumber from trees destroyed in Typhoon Yolanda can help to make the fences and supports in bunkhouse gardens.

As she walked around her bunkhouse’s garden, Lea Encina pointed out eggplant seedlings and lemongrass sprouts and chatted about what plants will soon be able to be harvested and cooked, sold and shared with family and friends.

“We’ve harvested three times already,” Encina said. “We are waiting just a few more weeks for our next harvest.” ■