A Network of Support

The deadly storm, one of the most devastating typhoons on record, garnered millions of dollars in donations from around the globe, even from as far away as UCLA’s campus.

UCLA students dropped their spare change into jars tied with red ribbons on Bruin Walk and pledged money at a benefit concert last winter to support the millions of Filipinos who were struggling to survive after Typhoon Yolanda struck last November.

In addition to supporting relief efforts, those donations helped build a new midwife clinic, deliver more than 100 babies, distribute thousands of toilets and plant hundreds of gardens across the island of Leyte in the Philippines.

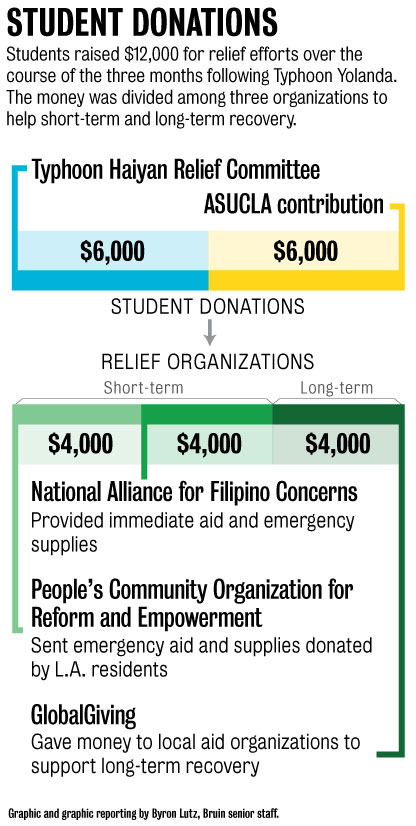

UCLA student donations targeted three relief strategies, as the $12,000 was split evenly between the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns, People’s Community Organization for Reform and Empowerment, and GlobalGiving – each of which had a fund dedicated to Typhoon Yolanda relief efforts.

People in and around Tacloban, the area that sustained the most damage from the typhoon, suffered for weeks after the disaster because their homes and belongings were washed away. Hundreds were buried in mass graves before any relief arrived.

Student groups said they will continue gathering funds throughout the 2014-2015 academic year to support long-term recovery efforts.

In the months following the storm, UCLA students, led by the Typhoon Haiyan Relief Committee, raised $6,000 to support typhoon recovery in the Philippines.

After a push from students earlier this year, Associated Students UCLA agreed to give up to $6,000 in late January, said Bob Williams, ASUCLA’s executive director.

During the first week of February, the store donated 10 percent of customers’ purchases when they presented a special coupon.

ASUCLA kept its promise. Students spent $60,000 for the cause, hitting the $6,000 cap within two days, Williams said.

Students had no control over the money once it left their hands – the spending was left to relief organizations both international and local in scope.

Directing relief

The $12,000, which mostly came from small donations of $5 to $20 and proceeds from the UCLA Store, helped thousands of people in the Philippines.

The money bought seeds for gardens where displaced people grow their own food, which allows them to save and earn money for permanent housing. It funded the delivery of more than 100 babies in the disaster zone and the rebuilding of a birth clinic that will continue helping women for years to come. The donations also bought emergency supplies that helped thousands of victims survive in the weeks after the storm.

While NAFCON and People’s CORE both prioritized emergency aid, People’s CORE also sent clothing and supplies donated by L.A. residents to the Philippines.

This aid was sorely needed in the immediate aftermath of the typhoon. People were without food for days, and sometimes the only source of nutrition was the fish swimming alongside corpses in the ocean, residents said.

“It’s hard to catch a fish swimming with dead bodies,” said local government official Gregorio Lantajo Jr. “Then you have to eat it. It’s hard.”

In the barangay, or small village, of San Joaquin about nine miles outside Tacloban, many more would have died without the intervention of international aid agencies, like those funded in part by UCLA students, that brought rice, sardines, noodles and tents, Lantajo said.

It’s hard to catch a fish swimming with dead bodies. Then you have to eat it. It’s hard.” —Gregorio Lantajo Jr.

Maharlika Gastones’ family lost everything to the floodwaters. Her family needed clothing right after the storm, along with gasoline, food and water.

So many people were left without any resources that looting started very quickly once the water had subsided.

People only took what they needed, Gastones said. They would find someone who could use a discarded item and pass it along.

“It was the best of times because the Filipino resilience came to the forefront,” Gastones said. “But it was also the worst of times because it was undignified to be stealing. But we had no choice.”

Until relief stabilized access to basic necessities, people were forced to find other ways to survive, Gastones said.

But months later, when food and shelter were easier to come by, the typhoon survivors needed another kind of relief effort – an investment in long-term recovery focused on rebuilding homes and livelihoods for people who lost everything in the storm. Student donations contributed to both types of aid.

It was the best of times because the Filipino resilience came to the forefront. But it was also the worst of times because it was undignified to be stealing. But we had no choice.” —Maharlika Gastones

L.A. connections, global implications

International aid organizations focus on monetary donations that can buy emergency supplies after a disaster, but local relief groups tend to target their grants toward a systemic problem in the area, such as housing, sanitation or food security.

But for both types of organizations, sending aid to a foreign nation isn’t without its challenges.

Vicki Penwell, the owner and cofounder of Mercy in Action, a group of midwives based in the Philippines that helped victims of the typhoon deliver babies, said shipments of medical supplies intended to help healthcare providers treat typhoon victims were stuck in customs for more than 10 months after Typhoon Yolanda.

In a stroke of luck for the volunteers who wanted to be part of an immediate relief response after the storm, the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns was already involved in relief work in the Visayan Islands of the Philippines because of an earthquake that had shaken the island of Bohol a month before the typhoon, said spokesman Jun Cruz.

The existing infrastructure allowed the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns to immediately funnel donations toward direct relief for hard-to-reach and deeply affected communities, Cruz added.

By focusing on monetary donations, the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns said it circumvented bureaucratic roadblocks. The monetary donations were allocated to three types of aid: relief packs, doctors and health services, and psychosocial intervention, Cruz said.

Although there were no official audits of charitable donations to the Philippines in the wake of Typhoon Yolanda, many of the groups UCLA students donated to say every dollar went to helping victims of the typhoon. To accomplish this feat, some groups said they relied on volunteer work to reduce overhead costs.

People’s CORE said it made sending the full amount donated toward relief to the Philippines a priority. The organization’s seven staff members worked on the group’s relief drive on a voluntary basis alongside about 20 community volunteers, collecting monetary donations, clothing and other basic supplies to send to the Philippines. The National Alliance for Filipino Concerns is also run by volunteers.

People’s CORE had ties to UCLA’s Samahang Pilipino before the typhoon, which was a factor in the $4,000 donation it received from the club, said program manager Christine Araquel-Concordia. The two organizations have teamed up to mentor high school students in Historic Filipinotown in Los Angeles.

Together, they have also worked on educational programs to inform people about challenges facing the Filipino community in the United States and abroad, including community health, Araquel-Concordia said.

Similarly, members of Samahang Pilipino said they have worked with the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns in the past, and their relationship contributed to the donations given to the alliance.

Donations through People’s CORE went to relief organizations like UNICEF and some grassroots organizations that were prepared to distribute immediate aid in the first few months after the disaster, Araquel-Concordia said.

Samahang Pilipino sold bracelets and shirts printed with its 2014 campaign slogan “Bayanihan,” which means “the spirit of communal unity to achieve a common objective.”

International concern and local solutions

The third organization UCLA students donated to, GlobalGiving, focused on funding local efforts to address lasting problems caused by the typhoon, such as access to fresh water and food, availability of housing and the ability to earn a steady income.

The organization allows donors to provide funding for much smaller charities in the Philippines. These smaller organizations tend to have long-term plans to provide aid but struggle to offer emergency relief because of their size and lack of resources.

Britt Lake, director of programs for GlobalGiving, said the group disbursed funds to organizations working on disaster relief within a week of the typhoon.

The first donations went to groups like Save the Children and International Medical Corps, but in the following months, GlobalGiving started dispersing money to local Filipino organizations instead of international charities.

From the almost $1.6 million typhoon relief fund, GlobalGiving gave money to Mercy in Action and the Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation.

Lake said GlobalGiving plans to keep matching funds for organizations like Mercy in Action and the WAND Foundation on the one- and two-year anniversaries of the typhoon to support ongoing recovery efforts in the Philippines.

UCLA Mabuhay Collective said it plans to continue its fundraising this year in order to provide aid to the recovering Filipinos on the other side of the world as they continue the long effort to rebuild. ■