Fading Funds and Continued Efforts

LEYTE, Philippines — Tents with fading international relief logos dot the nearly 70-mile stretch of roadside from Tacloban to Ormoc City in the Philippines, housing families with nowhere else to go.

Eleven months after Typhoon Yolanda hit last November, the names of international charities like the United Nations refugee agency, American Red Cross and Samaritan’s Purse are still visible in the affected areas, even if their efforts are waning.

International charities are slowly pulling out of the country as emergency relief becomes less needed, leaving local organizations to develop long-term recovery strategies.

Last year, thousands of concerned UCLA students handed over their dollars and change to help support a recovery effort on the other side of the world in the wake of the typhoon.

Yet few students know what happened once the money left their pockets.

The Typhoon Haiyan Relief Committee, which was composed of many UCLA student groups, organized a drive that allowed UCLA students to donate to the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns, People’s Community Organization for Reform and Empowerment and GlobalGiving.

While NAFCON and People’s CORE targeted their donation drives toward emergency relief provided mostly by large international aid agencies, GlobalGiving focused more heavily on funding local Filipino organizations.

The $4,000 that UCLA students allocated to GlobalGiving made up a modest portion of the organization’s overall Super Typhoon Haiyan Relief Fund.

The fund gathered nearly $1.6 million. Though GlobalGiving provided a series of grants to international aid agencies, it reserved much of the money for allocations to local grassroots charities that support lasting relief and recovery efforts in the Philippines.

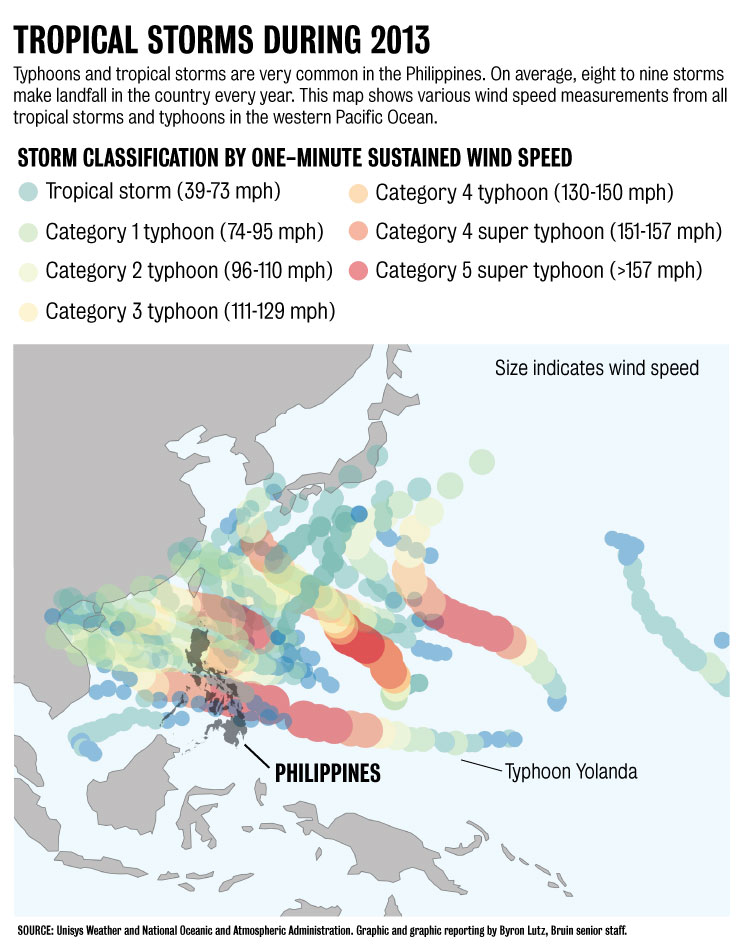

How Typhoon Classifications Are Determined

Typhoons in the western Pacific Ocean are categorized using the Saffir-Simpson wind scale to estimate the storms’ damage if they hit land. The scale has five levels of intensity, numbered one through five, with each level causing roughly four times as much damage as the previous.

Storms are categorized by measuring their one-minute sustained wind speed at 33 feet above ground. In addition, storms with sustained winds over 150 mph are classified as “super typhoons.”

Though this classification helps estimate damage from the storm’s winds, many other factors, like storm surges and building regulations, can drastically affect the storm’s actual damage.

SOURCE: National Weather Service. Reporting by Byron Lutz, Bruin senior staff.“Until March, most or all of the (U.N. aid agencies) were providing lifesaving items,” said U.N. refugee agency spokesman Keneath Bolisay. Not until five months after the typhoon did long-term recovery providing permanent housing, livelihoods and health resources to the millions displaced by the storm start at a large scale, he added.

The U.N. refugee agency, which made a massive push to distribute tents, solar-powered lanterns and other nonfood items within days after the typhoon, has reduced its on-site staff in Tacloban from 72 members to fewer than 10 since the storm, Bolisay said.

The type of emergency aid that these large international organizations provide isn’t needed in the Philippines anymore. People have access to food, the economy has stabilized and prices have returned to normal levels for necessities like gasoline and water. In some places, the Philippine government is building permanent housing for people displaced by the storm.

But in Leyte, where roads are still being reconstructed and the bent steel skeletons of buildings loom over piles of cracked concrete, life is not yet back to normal.

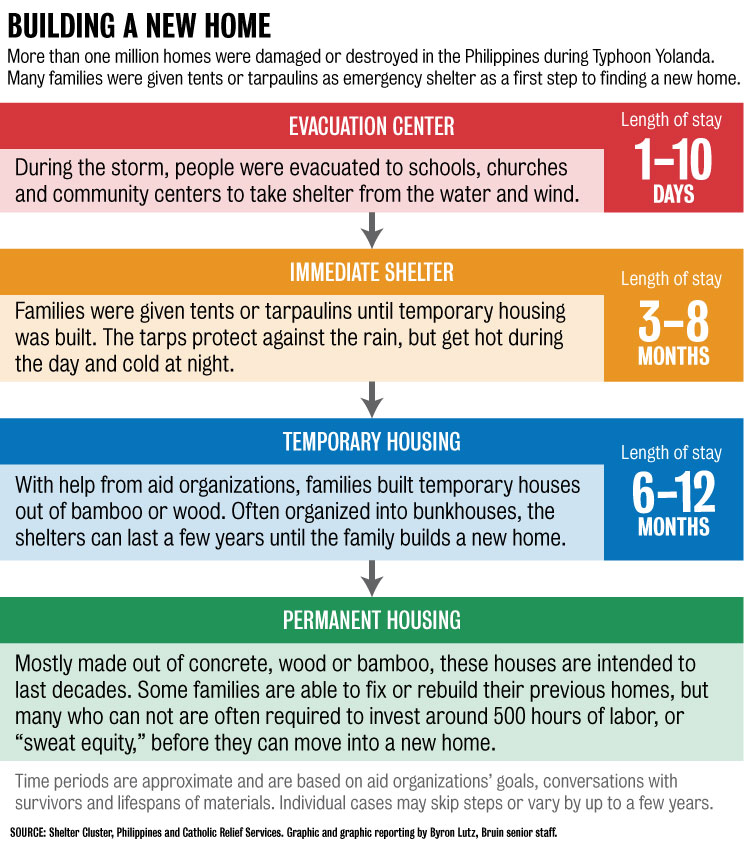

More than two million people do not have adequate housing, a visible problem on the streets of cities in Leyte. Many who were displaced by the typhoon still live in the same emergency tents that the U.N. refugee agency distributed almost a year ago.

Many people couldn’t return to what was left of their homes after the typhoon – and even now, many still cannot build on their properties because of government-enforced “no-build zones” that attempt to keep people away from the dangerous shoreline.

“Most displaced families came from coastal areas, where they can’t go in and rebuild,” Bolisay said.

These people, along with others with nowhere else to go, ended up in bunkhouses, where they may stay until they can afford to build new homes away from the coast.

On the outskirts of Tacloban, temporary housing units line the horizon. About 60 families live in one cluster of bamboo shacks. Although the temporary housing is not ideal, the refugees who fill the settlements no longer live in the flimsy tents that have outlasted their six-month expiration date.

Workers construct permanent homes for displaced victims of Typhoon Yolanda. Many workers are displaced victims themselves, putting in the 500 hours of “sweat equity,” or labor, needed to obtain housing.

Those who managed to obtain temporary housing have been living there for six or more months. The single-room bamboo units are meant for six- to 12-month stays, but the prospect of permanent housing remains months or years away for many families stuck in the bunkhouses.

Some families have new, government-sponsored houses ready to live in, but the officials who control them require 500 hours of labor, a practice called “sweat equity,” before residents can move in. Yet the rules surrounding the mandatory labor are not always clear.

The Lacaba family spent hours nailing woven bamboo sheets to wooden supports to build their temporary housing development, after city officials promised the labor would count toward their “sweat equity” total and allow them to move into their permanent residence much more quickly.

If the city housing would stick to their promises, we would already have our 500 hours.—Algina Lacaba

But miscommunication between the people in charge of temporary housing and permanent housing resulted in delays, said Algina Lacaba, who lived in Tacloban before she lost her home in the storm.

“If the city housing would stick to their promises, we would already have our 500 hours,” she added.

Working for four or five hours a day, Lacaba said her family has accrued more than 200 additional hours, but still has several more months of building before they can move into a permanent home.

And housing is just one difficulty facing the people of Leyte.

We don’t have a livelihood. We don’t have a fixed income to support our needs. —Algina Lacaba

Many also lost their livelihoods in the storm. Businesses were crushed and entire groves of coconuts, the primary export of Leyte, were destroyed.

Even though her husband has some work, Lacaba’s family is having trouble making ends meet after losing everything to Typhoon Yolanda.

How storm surges are created

A storm surge is created when a storm's wind creates vertical circulation in the ocean's water. When the storm gets close to land, the shallow sea floor pushes the water up and can create a large, tsunami-like wave.

The storm surge height in Tacloban during Typhoon Yolanda was estimated to have been around 10 to 20 feet.

Since so many factors – tides, wind angle, pressure and more – affect the flood's height, surges are difficult to predict and are not taken into account when determining a storm's classification.

SOURCE: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Reporting by Byron Lutz, Bruin senior staff.Before the storm, she was a credit analyst and was also qualified to be a teacher, but now she said there are no jobs for her to take.

Her husband’s job at the bus station pays far less than it used to. Instead of a regular paycheck, Joel Lacaba’s pay depends on the number of bus passengers. Because so many lost everything in the storm, fewer people have the means to use the transit system.

“We don’t have a livelihood,” Lacaba said. “We don’t have a fixed income to support our needs.”

The Lacabas share this problem with many others displaced by the storm. About 5.9 million people lost their source of income after the typhoon, according to the United States Agency for International Development, the U.S. government’s relief organization.

Small local charities say that’s why their efforts in the next stage of recovery are still so important.

UCLA students, through the GlobalGiving organization, donated to several local agencies – including Mercy in Action and the Water, Agroforestry, Nutrition and Development Foundation – that have plans to continue their recovery work for many years.

They should have asked me what they need, because we are wasting resources. —Gregorio Lantajo Jr.

Part of that recovery work comes in the form of rehabilitating services that were destroyed by Typhoon Yolanda.

Gregorio Lantajo Jr. is the San Joaquin barangay’s chairman, a position similar to the mayor of a small town. He said that many international nongovernmental organizations came to his community with good intentions, but their misconceptions about the residents caused problems.

“Many NGOs focused on the fisher folks,” Lantajo said. “But help for the coconut farmers was too little.”

One organization gave fishing nets to more than 100 men in San Joaquin, he said. There were then too many people fishing in a limited space, because former coconut farmers were pushing themselves to become fishermen.

“They should have asked me what they need, because we are wasting resources,” Lantajo added.

Knowing about the communities targeted by recovery aid can prevent oversights or redundancies in distributing resources, which is what makes organizations at the local level a valuable asset, said Yen Pham, a 2009 UCLA alumna working with Samaritan’s Purse.

Local charities, including those funded by UCLA donations, are situated particularly well to offer lasting impact in the area devastated by Typhoon Yolanda because they have an understanding of people’s needs, Pham added.

Near Ormoc City, WAND plans to be involved with at least three years of rebuilding efforts, such as providing toilets and seeds to people displaced by the storm, said in-house adviser Elmer Sayre.

The recovery efforts of local relief agencies are just beginning.

For the millions of Filipinos still feeling the effects of Typhoon Yolanda, the rehabilitation and recovery efforts will go on for years to come.

The UCLA Mabuhay Collective said its efforts to support aid in the Philippines will also continue, at least for the upcoming academic year. The student group is planning a memorial in November for victims of Typhoon Yolanda to recognize the one-year anniversary of the disaster. ■